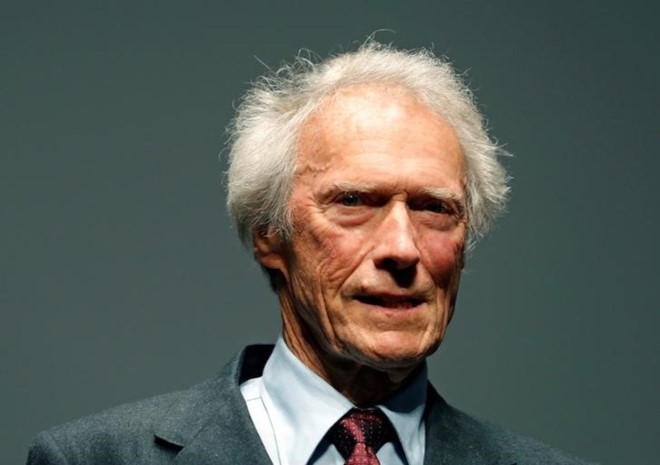

What Happened to Clint Eastwood At 95– Try Not to CRY When You See This

Here’s the quiet truth about Clint Eastwood at 95: the myth is intact, the man is thinning out at the edges, and the distance between those two things is where the real story sits. Strip away the YouTube bait—“try not to cry,” “shocking final chapter”—and you still have something worth listening to: a stubborn survivor who keeps working, keeps reflecting, and keeps refusing to turn his life into a tidy moral. If that disappoints you, he’d likely shrug. If it moves you, he’d likely change the subject.

The origin story is dusty and familiar, but the texture still matters. A Depression-era kid, ricocheting across California behind a father’s unstable work, learning early that attachment is a luxury and silence is a shield. The boy nicknamed Samson for his size grows into a tall, watchful young man who’s better at piano than small talk. That watchfulness becomes a craft. It’s the same quiet you notice years later on Rawhide, then in the Leone films, then in Dirty Harry: the pause is doing half the acting. It isn’t a gimmick; it’s a worldview.

There’s a near-mythic brush with death in 1951—an emergency water landing off Point Reyes, a long, freezing swim to shore—that reads like foreshadowing written by fate and later plagiarized by Hollywood. Whether you take it as a metaphor or just a harrowing anecdote, it tracks with what followed: a career built on economy. Fast shoots. Lean crews. Minimal takes. People called it efficiency. It also looked like a man who had learned not to waste what he couldn’t replace.

The ascent wasn’t glamorous. Bit parts, rejections, the wrong kind of face for that era’s idea of charm. Then Rawhide opens a door. The Man With No Name kicks it wider. Suddenly the quiet becomes marketable. Audiences develop a taste for the spaces between lines. We still talk about that as luck. It’s not. It’s the moment an unpolished thing arrives just as the culture gets bored with polish.

But here’s the inconvenient part: legends don’t stay legends by accident. Eastwood didn’t just star; he took control. Directing began as self-defense—Play Misty for Me was a way to stop other people from telling him how to feel—and became his real voice. Unforgiven in ’92 is the sermon he never gave: the West as a ledger of violence and regret, heroism stripped of hero worship. Million Dollar Baby and Gran Torino added quieter rooms to the house: old men forged by damage and duty, stumbling into grace without pretending they deserve it. He’s allergic to neat endings because he’s suspicious of neat lives.

That suspicion bleeds into the personal file, which is messier and less cinematic than the myth wants. Long relationships, longer shadows. A first marriage that couldn’t survive success or his restlessness. A stormy, public partnership with Sondra Locke that turned into years of courtroom fallout and private recrimination. Other relationships, other children, some acknowledged late, some kept at a dignified distance. The family map looks like a constellation—visible, even beautiful from afar, complicated up close. He’s present in moments and missing in others. You can argue with the choices; you can’t argue with the pattern.

If you’re tempted to hand him a late-life redemption arc, he doesn’t take it. He kept working into his 80s and 90s—The Mule, Cry Macho—films that sit with age rather than trying to outpace it. They aren’t bulletproof. They don’t need to be. The point isn’t perfection; it’s persistence. For a man who made a career of control, the later films read like a negotiation with the one thing he can’t direct: time.

Carmel-by-the-Sea is his base, Mission Ranch the sanctuary. He restored it decades ago, and it doubles now as a museum of his routines: the lean meals, the quiet exercise, the predictable walks, a piano waiting for hands that don’t need to prove anything anymore. You hear about a partner in recent years who brought gentleness instead of spectacle—and then about loss, again. That’s the rhythm of old age if you let yourself live that long. The headlines pitch tragedy. What you actually see is attrition and stubbornness playing out in parallel.

People close to him talk about alertness wrapped in remove. He sits slightly apart at family gatherings. He listens more than he engages. It’s tempting to pathologize that—call it loneliness, call it guilt, call it punishment. I think it’s consistency. He learned early that silence protects. It doesn’t always connect, but it keeps the edges from fraying. If there’s regret in the room—and there must be—he lets the work confess what the man won’t. He’s been doing that since the first day he stepped behind a camera.

Let’s talk legacy without the marble. There are the obvious markers: a genre rerouted, a directing style that made thrift feel like elegance, a gallery of characters who gave shape to the American appetite for lone wolves and private codes. But the subtler legacy is tonal. Eastwood taught audiences to trust the pause. To let a look carry meaning. To accept that morality in grown-up stories doesn’t speak in complete sentences. That matters in a culture addicted to speeches.

What about the off-screen ledger? The relationships. The children. The accusations of control or distance. It’s all part of the one truth he rarely decorated: he is not the men he played, only their curator. When he said, “I don’t like neat endings,” he wasn’t just talking about movies. The people who wanted Eastwood the patriarch, the confessor, the public penitent—he never promised that. What he offered instead was craft so honest it felt like confession. For some, that’s enough. For others, it’s a dodge. Both positions are defensible.

At 95, he looks like a man in a house where every object has a story, and some of those stories hurt to touch. Health rumors come and go. He moves slower. He works when there’s something he wants to say and goes quiet when there isn’t. He doesn’t perform frailty for sympathy or vitality for reassurance. He’s not interested in your catharsis.

Maybe this is the part where a magazine profile would force a reckoning—ask the children for quotes, tally the settlements, hunt down the tearful apology. That’s not the piece I’m writing, because it’s not the life he lives. The through-line is work and the discipline that makes it possible. The cost is emotional distance that shows up on holidays and in the blank spaces of old photo albums. The exchange is imperfect. Most are.

If you visit Mission Ranch in the late afternoon, the light does that generous California thing—it forgives more than it should. You can picture him on the porch, script in hand or nothing at all, not brooding so much as taking inventory. He’s not telling you a story. He’s deciding if one more is worth telling. He’s earned that decision. He earned it the hard way: by outlasting his mistakes and refusing to pretend they weren’t his.

Here’s where I land, after all the noise: Clint Eastwood’s final act—if we insist on “final”—isn’t a grand bow or a public unburdening. It’s a tapering into proportion. A man who built an empire out of understatement is living the ending he authored long ago. Fewer words. Cleaner lines. No victory laps, no televised mea culpas. Just the discipline to keep showing up to his own life, even when it asks more than he wants to give.

The myth is useful. The man is instructive. And between them is a lesson he’s been quietly handing us for seventy years: courage doesn’t always roar. Sometimes it just keeps going, one unremarkable day after another, until the work feels like truth and the truth doesn’t need a speech.