I have a clear and oddly vivid memory from childhood of noticing a distinct scar on my mother’s arm.

It sits high up, close to her shoulder, in a place that seems deliberately chosen, as if it were meant to be seen but not constantly noticed.

The scar has a unique shape: a ring of small indents arranged around a slightly larger one in the center. Even as a child, I knew it wasn’t an accident or an ordinary scrape.

It looked intentional, almost symbolic, like a mark with a story behind it.

I don’t remember why that scar captured my attention so strongly all those years ago. Children are often drawn to details without knowing why.

Maybe it was the unusual pattern, or maybe it was the way it stood out against otherwise smooth skin. Whatever the reason, I remember being aware of it, thinking about it, and wondering what could have caused something so precise.

As often happens with childhood curiosities, the question eventually faded into the background of my mind.

Of course, the scar itself never disappeared. It remained exactly where it always had been, unchanged by time. What disappeared was my fascination with it.

I forgot that I had once been deeply curious about its origin. Perhaps I even asked my mother about it back then, and perhaps she explained.

If she did, though, the explanation didn’t survive the many mental rewrites of memory that come with growing older. The question slipped quietly into obscurity.

Years passed without another thought about it.

Then, one summer several years ago, something unexpected happened. I was helping an elderly woman off a train, offering my arm as she stepped down carefully.

As she adjusted her grip, I caught sight of her upper arm—and there it was. The exact same scar. Same location. Same circular pattern. Same unmistakable appearance.

The sight stopped me in my tracks.

Suddenly, that old childhood curiosity came rushing back, sharper and more urgent than before. Seeing the scar on someone else made it impossible to dismiss as coincidence.

Clearly, this wasn’t unique to my mother. It was something shared. Something historical. Something deliberate.

I wanted to ask the woman about it right then and there, but the train was already preparing to continue its journey, and the moment passed too quickly.

Instead, I did the next best thing. I called my mother.

When I described what I had seen, she laughed gently and told me that yes, she had explained the scar to me before—more than once, in fact.

Apparently, my younger brain had decided the explanation wasn’t important enough to store permanently. The scar, she said, came from the smallpox vaccine.

That answer opened a door to a much larger story.

Smallpox was once one of the most feared diseases known to humanity. Caused by the variola virus, it was highly contagious and often devastating.

The disease typically began with fever, fatigue, and severe body aches, followed by a distinctive rash that spread across the body. The rash evolved into fluid-filled blisters that eventually scabbed over, often leaving deep, permanent scars.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), during the height of smallpox outbreaks in the 20th century, approximately 3 out of every 10 people infected with the disease died.

Those who survived were frequently left with lifelong disfigurement, including pitted facial scars and, in some cases, blindness. Entire communities lived in fear of outbreaks, and families could be wiped out within weeks.

For centuries, smallpox shaped human history. It influenced wars, altered populations, and affected the course of civilizations. No one was immune to its reach.

The turning point came with the development and widespread distribution of the smallpox vaccine.

Unlike many modern vaccines, the smallpox vaccine was not based on a killed or weakened form of the virus itself, but rather on a related virus called vaccinia. This virus stimulated the immune system to recognize and fight smallpox without causing the disease.

Thanks to coordinated global vaccination efforts, smallpox was gradually pushed back. In the United States, the disease was effectively eliminated by 1952.

Routine smallpox vaccinations continued for several more decades, but by 1972, they were no longer part of standard immunization schedules for the general public.

In 1980, the World Health Organization officially declared smallpox eradicated worldwide—the first and only human disease to be completely eliminated.

For people born before the early 1970s, however, the vaccine was a routine part of childhood. And it left behind a visible reminder.

Up until that time, nearly all children received the smallpox vaccine, and it almost always resulted in a permanent scar.

In a way, it functioned like the world’s earliest vaccine passport: a mark that silently confirmed you had been protected against one of humanity’s deadliest diseases.

That scar—the one my mother bears, and the one I saw on the elderly woman’s arm—is a relic of that era.

So why did the smallpox vaccine leave such a distinctive scar?

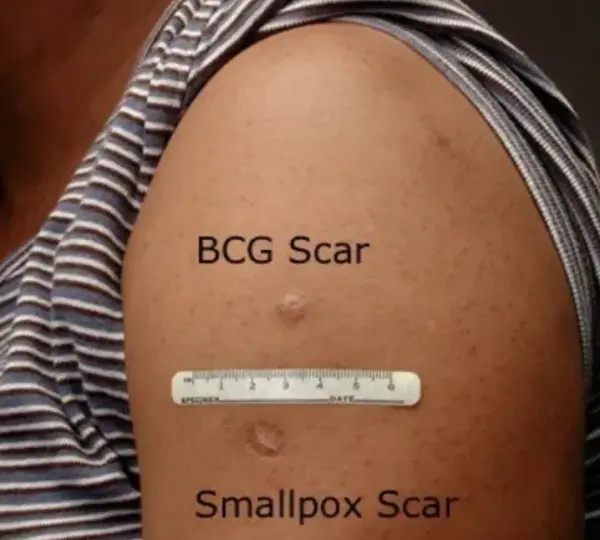

The answer lies in how the vaccine was administered and how the body responded. Unlike today’s vaccines, which are usually delivered through a single injection into muscle tissue, the smallpox vaccine was applied to the skin using a special two-pronged needle.

The needle was dipped into the vaccine solution and then used to make multiple quick punctures in the upper layer of the skin.

These punctures delivered the vaccine into the dermis, the layer just below the surface. Rather than being absorbed quietly, the vaccine triggered a localized infection.

Over the following days, a small raised bump would appear at the vaccination site. This bump would develop into a vesicle—a small, fluid-filled blister—which would eventually break open, scab over, and heal.

The entire process took several weeks. During that time, the immune system learned to recognize and defend against smallpox.

The visible reaction was not a side effect in the modern sense, but rather a sign that the vaccine was working as intended.

When the scab finally fell off, it left behind a scar. The size and shape of the scar varied from person to person, but it almost always followed the same general pattern: a circular indentation, sometimes surrounded by smaller marks from the needle punctures. Over time, the scar faded slightly but never disappeared.

Today, that scar serves as a physical reminder of a battle humanity won.

It’s easy to overlook the significance of such marks in an age when many deadly diseases are no longer part of everyday life.

Modern medicine has made it possible to forget how vulnerable humans once were. But the smallpox scar tells a story of fear, resilience, and collective action.

It represents a moment in history when science, cooperation, and persistence overcame a threat that had plagued humanity for thousands of years.

Seeing that scar now feels different than it did when I was a child. What once seemed mysterious now feels meaningful.

It’s not just a mark on the skin; it’s evidence of survival, of progress, and of a shared human effort that transcended borders and generations.

That moment on the train reminded me how easily we forget the struggles that shaped the present. Diseases that once defined entire lifetimes have been reduced to footnotes in history books.

But for those who lived through them—or through the efforts to eradicate them—the memory remains, sometimes literally etched into their skin.

My mother’s scar is a small thing, easy to miss unless you know what you’re looking for. But now, when I see it, I don’t just see an old mark. I see a chapter of medical history.

I see proof of what coordinated public health efforts can achieve. I see a reminder that the comforts we take for granted today were earned through decades of research, sacrifice, and trust in science.

And every so often, when I notice that familiar circular pattern on someone else’s arm, I’m reminded that we carry history with us in ways we don’t always recognize—quietly, permanently, and meaningfully.